Lost Houses of Derbyshire – Old Radburne Hall

By Maxwell Craven

One of the most delightful, sequestered and ancient parish churches in the county is that of St. Andrew, Radbourne, set beside the Radbourne Brook (effectively a tautology: the clue is in the name, the ‘red bourne’, or stream) in a hamlet which hardly seems to exist, despite being barely four miles from Derby. It is well hidden from the unfrequented road, although well signposted.

As you descend the path to the church you can see across a broad pasture to the brook and the ridge beyond, atop which stands the fine Georgian mansion that is today’s Radburne Hall (the spelling differs from that of the settlement, by hallowed tradition), although it is slightly beyond one’s eye-line. The pasture itself is full of strange hollows, and was originally the site of the first known houses on the site.

Radbourne is one of those rare landed estates: one that has never been sold since its first recorded owner obtained it. It has, however, passed via an heiress four times since its first record, the first three in the Middle Ages, the fourth currently, but the blood of the first recorded tenant, Wakelin de Radbourne – who is on record for 1100, but was almost certainly the 1086 (Domesday Book) tenant – still flows in the veins of the incumbent family. Who exactly Wakelin was is not clear, although it has been suggested that he was reasonably close kin to his overlord, the tenant in chief, Henry de Ferrers, lord of an hundred Derbyshire manors, other members of whose family certainly used the name.

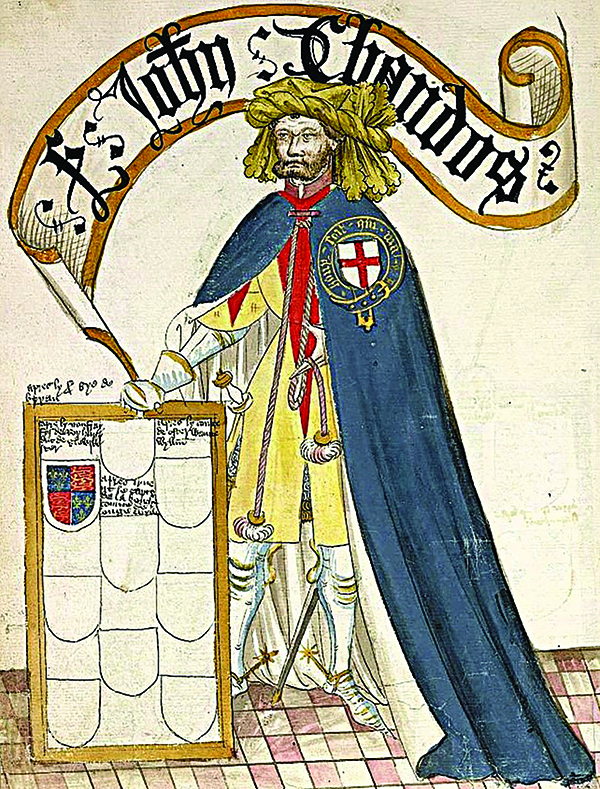

The monumnet to Sir John, now at Mazerolles

The grandson of Walkelin left no son but a daughter and heiress, who married John de Chandos who was of a minor gentry family from SW Herefordshire, Chandos being a locality in Much Marcle parish in that county. John’s great-great-grandson was Sir John Chandos, KG, the great hero of the Hundred Years’ War, Constable of Aquitaine and Seneschal of Poitou, created by Edward III Viscount St Saveur-le-Viscomte in the Contentin in 1360. Sir John, born around 1320, was a close friend of the heir to the throne, Edward, the Black Prince and, in 1348 joined his patron in being nominated one of the first ever Knights of the Garter.

Described by the medieval historian Froissart as ‘wise and full of devices’, as a military strategist, Chandos is believed to have been the mastermind behind three of the most important English victories of the Hundred Years War. He was chief of staff to the Black Prince at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, was a leading commander a decade later at the Battle of Poitiers and also in the Battle of Auray, in the War of the Breton Succession in 1364, following which his commander, John Duke of Montfort, was able to succeeded as John IV, Duke of Brittany. In addition to his other honours, Chandos was created the lieutenant of France and vice-chamberlain of England.

In 1369, the French launched a successful counter-attack, regaining much territory and forcing Edward to recall the retired Chandos, who attempted to deal with the French attempts to regain a foothold in Poitou, of which he was made governor. In a skirmish following an unsuccessful attempt to re-take St. Savin, Chandos met the French on the bridge at Lussac. In the ensuring melée, Chandos’ long coat led to him slipping on the frost. James de Saint-Martin, a French squire, struck Chandos with his lance, piercing his face below the eye although Chandos’ uncle, Edward Twyford of Kirk Langley, standing over his wounded nephew, repulsed the attack. The wounded Chandos was carried on a large shield to Monthemer, the nearest English fortress, but died, unmarried, in the night, either on the 31st December or the early hours of New Year’s Day 1370.

Sir John Chandos as Knight of the Garter, 1348 from the Bruges Garter Book

Such was Sir John’s reputation that Charles V (‘the Wise’) of France is reported to have said that ‘had Chandos lived, he would have found a way of making a lasting peace’ although French chronicler Jean Froissart was more circumspect, saying ‘I have heard him at the time regretted by renowned knights in France; for they said it was a great pity he was slain, and that, if he could have been taken prisoner, he was so wise and full of devices, he would have found some means of establishing a peace between France and England.’

He added of Chandos that ‘Never since a hundred years did there exist among the English one more courteous, nor more full of every virtue and good quality.’

He certainly comes across much in the heroic mould of those other two hammers of the French, the Dukes of Marlborough and Wellington, although his reputation lost nothing in having been killed in battle.

The estate passed to Sir John Lawton, married to one of Chandos’s sisters, although the loss of the original patent creating Sir John a Viscount means that no one is sure whether it was remaindered to his sisters and their issue, failing any heirs of his body, or not. As a French title, albeit granted by the King of England (but as King of France), this may well be true, meaning that Lady Chichester might well be Viscountess de St. Sauveur. Certainly, his heiress brought all his property to her husband to Sir Peter de la Pole from Cheshire.

The Poles, too burgeoned mightily once ensconced in the county, for younger branches settled at Kirk Langley, Barlborough and in a moated house north of Hartington, now marked by a farmhouse called Pool Hall; one of this latter branch, John Pole, became the outlaw after whom Castleton’s Poole’s Cavern was (phonetically) named. Nevertheless the Radbourne Poles have been there ever since, although they assumed the additional surname of Chandos in the Regency period as homage to the enduring renown of Sir John.

At Radbourne Sir John is reputed to have had a ‘mighty large howse of stone…situated in the hollow by the brook’. It reputedly boasted 100 ‘beds’, stabling for 200 horses and vast cellars that flooded when the brook became high, resulting, as the late Maj. Chandos-Pole (quoting family tradition) told me that Sir John’s servants frequently had to fetch the sack and beer up from the cellars using empty casks as boats! The site was excavated about five years ago and some vestiges of it uncovered which confirmed that it was partly stone built, as is the adjacent church.

This house sounds mightily inconvenient, large or not, so the Poles eventually built a more conventional Elizabethan style residence on a nearby site, drawn in elevation for us by surveyor Thomas Hand in 1711. His drawing is a trifle formulaic-looking, but we know from his other elevations on estate plans that they all varied, so probably his image reflected much of what he saw.

The house’s facade appears to have been three double bays wide, with string courses over the windows to divide the floors, as had become fashionable since the building of Hardwick. It was of three storeys with attic gables above that, too, suggesting something of a Derbyshire-style tower house, much favoured in the wake of the building of Buxton Old Hall in the later 16th century, which would in turn imply that the state rooms may have been on the second floor, also as at Hardwick. The gables, inevitably, were punctuated by tall chimneys. Hand’s plan also shows 10 acres of gardens, orchards and yards to the west.

The size of the house is confirmed when we find that it was assessed for hearth tax in 1664 on a fairly generous 20 hearths, and was further rebuilt by Samuel Pole (died 1731), after he had inherited from a distant cousin, in 1683, although exactly what was done, is not clear.

His successor, the excellent German Pole, Tory, Jacobite and would be MP for Derby in 1741 decided that, having been thwarted in his political ambitions, he would replace the old house in favour of a new one, to be built of brick on top of the ridge south of the church, which duly happened in that same decade, most handsomely and to the designs of William Smith of Warwick. German Pole’s widow was the last resident in the old house, whilst her husband’s successor, Col. Sacheverell Pole occupied the new one. It was abandoned in 1753 when Mrs. Pole died, but was kept, probably in case it was required as a dower house again.

Yet, when James Pilkington was writing his history of the county in the 1790s the old building was reported to be ‘now in ruins’ and was probably cleared entirely in the wake of William Emes’s re-landscaping the parkland, begun in 1791, in which it lay. Some oak wainscot was, however, recovered from it and was re-used in two rooms of the present house, probably installed during its rebuilding in the Regency period.

Now only the undulations in that amiable pasture remind us of past glories, when Sir John Chandos lived there (when not knocking seven bells out of the French), next to the church.